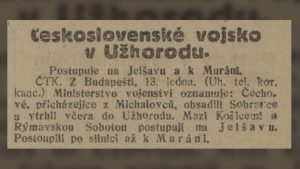

On a Sunday afternoon, 12 January 1919, Dr. Szőke Andor, Ungvár’s (Uzhhorod’s) chief medical officer was dozing in a car that took him from Szobránc (Sobrance) to Ungvár. Dr. Szőke was travelling with people of high rank, Berzeviczy István Ungvár’s mayor, and Bánóczy Béla Ung County’s recorder. This time, not the chief medical officer’s curative skills were needed, but his knowledge of Italian. He visited Szobránc as an interpreter, a member of a delegation from Ungvár and met Amadeo Ciaffi, an Italian colonel, who came to the Ung County town heading an approximately 1200 Czechoslovakian legion. The subject matter of the discussion was Ungvár’s Czechoslovakian occupation. Ungvár delegation drove directly to the county hall where the Italian colonel arrived soon in a rented car. The media of the period wrote that the bystanders were positively impressed by the Italian military’s appearance and manners. The Italian Czechoslovakian legionaries in uniform interested the population of Ungvár for they sang marching songs in an unknown language and had feathered hats. This way started Transcarpathia’s Czechoslovakian military occupation that became official in September 1919 after concluding the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and started stabilizing the new civil administration. In one part of Máramaros (Maramureș) County Romanian troops were stationed till summer 1920 when the Treaty of Trianon was signed. Following this, the new state expanded its sovereignty over the entire Transcarpathia. We know other scenes of the Czechoslovakian control as well and they differ from those described above. The most shocking, unquestionably, tragic event happened on 7 March 1919 when an argument resulted in killing of journalist Pós Alajos by the Czechoslovakian military in an open street. A similar Transcarpathian war-time incident was described by Pálóczi Horváth Lajos in his novel “On the Border of Two Worlds” Having been told that they belong to Czechoslovakia already, the citizens who gathered in Beregszász (in the novel – Porogjász) county hall burst into tears and sang the Hungarian anthem, while the French general who was making the announcement stood at attention and listened to it till the end. Archive sources testify to the fact that this really happened. General Hennoque’s Beregszász visit was interrupted not only by singing the anthem but also by flying the Hungarian flag on the county hall. The city’s deputy mayor had to be liable to the military authorities for the symbolic disturbance. Marina Gyula, a Greek Catholic canon who emigrated to the US recalled that the Greek Catholic Ruthenians from Lonka village observed one Sunday that while they woke up in Czechoslovakia, their church on the other bank of the Tisa River now belonged to Romania. The people of Lonka village paid no heed to international agreements and threw the temporary wooden border gate on the bridge across the Tisa into the river. This way they made a breach in the Treaty of Versailles construction for the period of a Sunday liturgy.

After the Great War, numerous states laid claim to the territory later called Transcarpathia. Naturally, Hungary wanted to keep its north-eastern counties, however, Czechoslovakia, Romania and the unfolding Ukrainian statehood as well claimed a part of or all of the territory. Moreover, at the Paris peace conference, Poland emerged as another possible owner. The local population hardly knew anything about the plans or were totally unaware of them. At the turn of 1918-1919 everyday life was characterized by cracks in and withdrawal of the central government authority. At the same time, in the marginal regions of Hungary disorders grew, poor public supply and security, as well as epidemic diseases called for the local structures to take increased responsibility. Churches, county and municipal state officials, at the time of the People’s Republic the national councils, then at the time of the Council Republic the Directorates made attempts to overcome the situation that evolved. This can be explained by the fact that some people felt responsibility for the community, others were led by financial gain or other personal motives, or else a mixture of these. In essence, they tried to fill in the ever-greater abyss that was formed in place of the hardly ever present government authority. With varying success. A good example for the functioning of the local authorities is the case of Beregszász (Berehove) warehouse. In summer 1919 the Czechoslovakian military, who took over the town, started an investigation to find out what resulted in complete exhaustion of the town’s reserves. It turned out that, first of all, Beregszász Directorate used the goods reserved for hard times, then the Romanian military used them to provide for their own supplies. Beregszász citizens carried away the rest. The emerging of the new state structure started with the military expansion. The Romanian and Czechoslovakian armies’ action against the Hungarian Council Republic, then the gradually spreading Czechoslovakian military control made the Hungarian community face a completely new situation. The Hungarians’ reaction was surely influenced by two things. The first is the above-mentioned public administration chaos they experienced. The Czechoslovakian arrangements brought about consolidation, both in economic and political sense. Ensuring public supply and order indisputably contributed to the fact that, basically, the Transcarpathian Hungarians peacefully accepted taking over of power. Another factor according to historians and the evidence of people who witnessed the events was that the local Hungarian community members did not believe that the occupation and, thus, breaking away from the Hungarian state would become perpetual.

On the territories occupied by the Czechoslovakian army city administration made announcements to the population informing them that “military dictatorship” came into force. The local state officials kept their posts and each made an oral pledge to continue doing their duties. Following the occupation, the town and municipal council, a significant part of settlements’ civil servants stayed at their posts till the end of the year and performed their duties trying to adapt to the evolved situation. Nagy Ernő, former Alsóverecke (Nyzhni Vorota) chief constable of a county, deputy-lieutenant of Bereg County at the time of the occupation, told in 1922 that in summer 1919 the military commanding officer demanded a verbal pledge from all government employees that they would not leave their offices and would maintain order: “The general mood was that everyone should stay at their posts, […] to prevent foreigners coming to the vacant positions.” Side by side with military occupation public administration reorganization started. In the summer of 1919 zhupas were formed instead of counties, headed by zhupans. It was typical of people who had some public role under Hungarian control to contribute to the building of Czechoslovakian public administration. For instance, Bereg zhupa’s first zhupan was Kaminszki József, former secretary to minister of Szabó Oreszt Ruska Kraina and political delegate of Ruska Kraina at the time of the Council Republic. In Ungvár the situation was different. After the occupation a Slovak state official, Ladislav Moyšt was appointed there as zhupan by the Slovak plenipotentiary minister Vavro Šrobár. There were no significant personal changes in the settlement’s public administration between July and December 1919. In compliance with the Hungarian Kingdom’s laws public administration functioning was performed by the former government officials until 1 December 1919 when the Czechoslovakian civil administration was formed.

Dozens of posters were placed in the streets of Transcarpathian settlements almost on a weekly basis by means of which the military headquarters wanted to inform the population of their changed situation. After the occupation, the first edict the local population was faced with was about frontier control. In practice, a neutral zone was established between the territories occupied by the Czechoslovakian armed forces and the territories that remained under Hungarian control. Checkpoints were established along the zone where the occupying military conducted frontier control. However, before the checkpoints were set up only official military and diplomatic mission representatives had the right to cross the border. After the checkpoints were set up, one had to obtain a travel permission to cross them. This could be obtained from the municipal councils, certified by the local military headquarters and the latter determined its period of validity. Those who arrived in the occupied territory had to visit the town or municipal council office to get a travel permission which they took back to the border to cross it. Naturally, there were many people who moved between the occupied and the neutral territories on a daily basis because of their work or official duties; they were given permanent passes. Frontier control regulated not only people’s movement but also transit of goods and personal effects. The nearest military headquarters could grant permission for the delivery of goods, however, it was forbidden, for instance, to deliver letters and newspapers across the border. The latter were confiscated and conveyed to the division’s commanding officer. Naturally, it was not easy to introduce a border regime overnight on a territory where there was no state border before. In 1919-1920 the authorities often reported that people crossed the borders without a passport or documents.

The troops and the military gendarmerie were responsible not only for frontier control on the occupied territories. They also tried to control maintenance of public order. They asked the local population to turn in the guns they had no permission for. There were numerous cases of perquisition related to it. In case the population did not cooperate or sabotaged, thus making the troops’ work harder, the Czechoslovakian army exercised punishments by means of preventive detention, hostage-taking decided by a draw. An edict was issued stating that people spreading Bolshevik ideas would be searched for and arrested. Moreover, as far as the edict was retroact, it concerned those people who contributed in any way to the building up of Soviet power in Beregszász. Thus, the territory’s military headquarters ensured the population in its communication of the legitimacy of the occupation, of the fact that the population was tied to the new republic by its “Slavonic kinship”. Furthermore, the military “troops came at the nation’s will as friends and it is advised that they be treated likewise.”

Árky Ákos, former army officer, one of the prominent figures of the Transcarpathian Hungarian oppositional political elite that was formed after WWI, called the Czechoslovakian military occupation months as “pacifying occupation” and the process following the stabilization of public administration as “conquest”. It is difficult to characterize from high-sounding declarations the differences between the stabilized functioning of Czechoslovakian civil administration after signing the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919 and the military occupation. However, it is a fact that the Transcarpathian Hungarians had less illusions after September 1919.

Szakál Imre

historian, lecturer, research staff member

Ferenc Rákóczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian College of Higher Education

This work is the sixth part in the collection of articles “The hundred-year-old Transcarpathia” initiated by Lehoczky Tivadar Sociological Research Centre of Ferenc Rákóczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian College of Higher Education.